Performative Patel

Kash Patel's new challenge coin and the actual performative male moment.

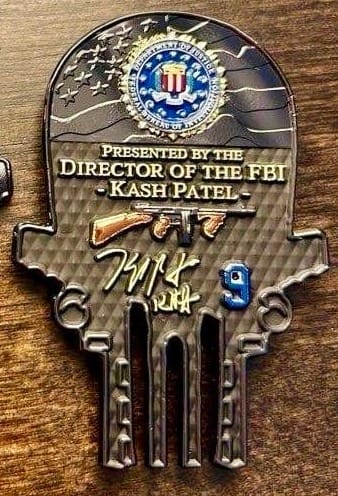

In early October, journalist Ken Dilanian posted an image of the two faces of an alleged new challenge coin issued by the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Kash Patel. The image of this new coin, shown below, speaks to a very particular strain of performative male — but at a national scale and from his seat at the helm of one of the world's most powerful state security forces.

Challenge coins don’t originate with Patel, of course. They’re medallions typically given in the military (though increasingly in militarized police forces) as a mark of esteem, often in the wake of an achievement or participation in a key operation.

The performance of gender, which I believe this coin deeply represents, has certainly seen a resurgence in common internet (and IRL) parlance. As a result, I think it’s important to consider recent discourse on the “performative male” before I return to this absurd coin.

The Performative Male and Popular Gender Anxiety

In late 2024, a new trend arose commenting on the performativity of select men, specifically those who describe themselves “male feminist(s),” often to get attention from women in urban and campus settings. Know Your Meme, per usual, has a great write-up of the evolution of this meme (mostly on TikTok), which includes performatively reading books like Sylvia Plath’s Bell Jar (often carried in a tote bag held rigid by a Clairo record contained within), wearing a labubu on one’s belt loop, and/or drinking matcha. Many male-identifying content creators were involved in the initial (comedic) crafting of this seemingly critical trend (from Jack “The Slappable Jerk” Ryan in 2022 to a man on Kareem Rahma’s “Subway Takes” in 2023 to Henry Grey Earls in early 2024) before it rose to prominence when multiple female TikTok creators adopted the phrase “performative male” and made meaning from it. The deluge of (almost exclusively tongue-in-cheek) videos of people pointing out (or making skits of themselves as) performative males was in full swing by the summer of 2025, when videos of “Performative Male Contests” popped up from Wicker Park in Chicago to Washington Square Park in New York City to Alamo Square Park in San Francisco to Georgia Tech in Atlanta. These gatherings were patterned after the ‘celebrity lookalike’ contests that took off last year and have, in turn, prompted a lot of interesting articles about gender trouble and queer pioneers.

This iterative critique of a softer masculinity (often meant or used to get the attention of or attract women) is the current, Gen Z version of what other generations might recognize as a ‘softboi’, a ‘hipster’, a ‘tryhard’, or similar derogatory descriptions. The terms for this phenomenon of weaponized soft masculinity often get meaner, more homophobic, and more direct as one retreats through past generations.

This brings us to the trend’s growing critique, often written by women: Kyndall Cunningham bemoans the reactionary tendency of “questioning the integrity” of men who dabble in feminine aesthetics, Syeda Khaula Saad notes how rejecting “performative males” reinforces “the very gender traps we’re trying to escape”, and Lydia Spencer-Elliott laments the trend as an example of cultural forces that could further exacerbate a clear and growing crisis of literacy among men. James Factora, writing for Them magazine, offers two key insights (even reaching out to Gender Trouble author Judith Butler) that seemingly stand in tension: 2020s meme culture is clearly both gender-obsessed and keen to escape from gender roles.

Elements of the Coin

Okay, back to the coin.

Tom Nichols, writing for the Atlantic, has pointed out the coin’s obvious similarity to the Punisher skull, a favorite icon of the Patriot Movement, weirdos in the military and police, and even for occupying Israeli soldiers in Hebron, Palestine. Patel’s own background shows he is deeply acculturated to both this specific culture and version of performative masculinity.

The Punisher skull may seem to be a silly, if not ironic, icon for military, state, or paramilitary actors to use. Punisher’s creator, Gerry Conway, has denigrated those co-opting his character’s symbol, noting the moral grey area that the Punisher represents. Indeed, the skull’s originating character, Frank Castle, frequently demonstrates his disdain for law enforcement, including through direct violence against officers. In episode 9 of the newest season of Daredevil: Born Again (2025), Jon Bernthal as the Punisher kills a TON of cops, and tells a task force of police officers wearing the skull that they’re “a bunch of clowns.” However, this isn't universal — in the 2004 Punisher movie, Castle is a retired undercover FBI agent, a detail that ends up being extremely crucial to the plot. It’s also worth mentioning that a previous FBI memo on “Militia Violent Extremism” identifies the Punisher Skull as an extremist symbol often used by these actors. In case this isn’t already clear, the Punisher skull, as a symbol itself, has a complicated and deeply contested history of meaning.

Further, the Punisher's creator has specifically said he was inspired by the SS Totenkopf when creating the symbol. The Totenkopf (German for “death’s head”) is a specific skull and crossbones symbol that is most commonly associated with the Nazi’s Schutzstaffel, specifically the unit tasked with guarding concentration camps and with the 3rd Panzer Division, a Waffen-SS combat unit many concentration camp guards were transferred into (and who committed numerous war crimes by the end of World War II). The Totenkopf has recently returned to popular media coverage after reports that Democratic US Senate candidate Graham Platner has had a tattoo of the symbol on his chest since 2007 (and, disturbingly, hasn’t thought to have the tattoo removed or covered up in the nearly 2 decades since).

In many ways, the Punisher skull has now lived a life well beyond its connection to the comic book character, much less the origins from which its creator drew. It is now part of a larger collection of icons signifying "tough guy" status. This is where performative masculinity is most clear in its influences on Patel’s decisions around this coin — the coin itself being a truly impressive example of how many different “tough guy” symbols it directly pulls from, further outlined below.

Below the nose of this Punisher-esque challenge coin is a helmet adorned with a crest. This is a bit of a symbolic mess, as the helmet appears to merge a slew of different historical helmets — the Corinthian helmet with its nose plate, the Chalcidian helmet with its cheek protection, and even the Roman galea helmet with its notable crest. All of these helmets, through a Frankenstein’s monster of historical references, have connections to popular “dude” culture, especially early 2000s movies about warriors in antiquity — like Gladiator (2000), Troy (2004), and 300 (2006). For what it’s worth, these images, identified as a collection of “warrior culture” icons, are also mentioned in that FBI memo I brought up earlier. This warrior culture touch-point is signified by these helmets, and is often accompanied with “Molon Labe”, Greek for approximately “come and take it” and usually attributed to Leonidas writing to Xerxes just before the Battle of Thermopylae. This Greek phrase has had multiple afterlives (translated versions were used in Georgia’s Fort Morris in the American Revolution, during the Texas Revolution, and by a Union Army colonel in Georgia against the attacking Confederate General Hood), but has seen a resurgence in the past few decades in the particular type of gun ownership marketed by the National Rifle Association.

Inside the skull’s eye sockets are insectoids that, at first glance, appear to be spiders. However, the body shape, specifically the lack of an unsegmented abdomen, makes it apparent these are actually mites or even ticks, not spiders. While there’s not a ton to say about spiders, other than they are often part of a broader grammar of edgy iconography and relatedly may have or deploy deadly venom, there’s much less to say about the unintended-yet-depicted mites.

The skull’s tines (evocative of teeth but indeed looking more like those from a dulled fork in this instance) are partially constructed by revolver barrels, whose triggers and sights are also embossed on the back of the coin. These revolvers appear modeled after either the Colt Python .357 or Colt Anaconda .44 revolvers, neither of which has been officially carried by FBI agents. Popular video games are more likely to be the source of these specific gun models, as the Python appeared in the first two Call of Duty: Black Ops games and the Anaconda in tons of games of the franchise, including when wielded by the antagonist in Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 (2009). Comparatively, FBI agents have historically mostly used .38 specials and occasionally a different .357, namely the Model 13, which bears very little resemblance to the Python or Anaconda.

This Call of Duty connection is, I think, a really important component of this coin’s dudecore lineage. I have a suspicion that the sentiments towards the U.S. military held by a lot of these martially-inclined, non-veteran Gen X (or Elder Millennial) men stem from either Call of Duty or the movies that influenced the video game series: Black Hawk Down (2001), Heat (1995), The Bourne Identity (2002) and its sequels, or even Red Dawn (1984) and the first Rambo movie, First Blood (1982). There’s even a feedback loop at work here, as the cinematic decisions of Call of Duty have inspired later movies like Lone Survivor (2013), which in turn likely influenced the 2022 reboot of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare II. All of these pieces of fiction have contributed to a canonical quagmire of contemporary dude media about the US military in particular and war in general.

The letters across the top of Patel’s coin say "K $ H," pronounced like the FBI director's first name. A few weeks back, another challenge coin from Patel was also posted online, with "KA$H PATEL" on the bottom, suggesting that his name’s missing vowel is a newer evolution. There's something very podcaster-coded in this design decision, and these podcasts are clear examples of a space rife with “dude culture” and coterminous with Patel’s strain of performative masculinity.

It is important, however, to note just how much performative “tough guy” content comes from or through podcasts. Accused rapist and trafficker Andrew Tate is only one toxic creator among many in this space, and some of the highest-paid people in media have been dude podcasters (case in point: Joe Rogan’s $250 million deal with Spotify). Patel, who came to fame in large part due to his podcast “Kash’s Corner”, has used this Corner to publicly craft his masculinist pro-Trump persona (while heavily criticizing the FBI he would later lead).

Turning to the back of the coin, we have fewer overall symbols, but some of the performative masculine components from the front carry over to the back, including the detailed shapes of the revolvers and the overall skull silhouette of the coin.

Here on the back, Patel's signature sits below a Thompson machine gun, a favorite among early FBI agents and Prohibition era gangsters alike. The FBI, as it exists today, would not have existed were it not for Prohibition, which led to this visual identification of the Thompson even a century later. The Tommy Gun was replaced in FBI service by the MP5, which is still in use in some cases but was deprioritized in 2002 in favor of 5.56mm rifles.

The bottom half of the back of the challenge coin also has a diamond pattern that looks marginally like the foam padding common in rifle cases. It’s unclear if this was intentional, so I won’t go into further depth.

Patel’s Punisher coin is just one of many coins he has issued, adding to a growing bricolage of physical tokens to and invocations of performative masculinity. His previous challenge coin was not nearly as gaudy as the Punisher one, but it did feature a Gadsden Flag merging into an American flag. The Gadsden Flag, at the risk of constantly citing that “Militia Violent Extremism” memo from the FBI, is also listed as “commonly referenced historical imagery” for the militia world.

We truly have come a long way in such a short time that this flag, once used exclusively by Tea Party-poisoned right-wing libertarians, is now featured alongside the seal of the FBI. This shift — from a rightist but nominal anti-state symbol to a symbol recuperated into state iconography by a follower of half-baked rightist politics — shouldn't be interpreted as hypocrisy, but instead should be interpreted through the lens of power. Those in activist spaces carry their aesthetics into positions of state power, which was a goal of many of these political operatives, including Patel, from the beginning. They are purely aesthetic signifiers, a sign of a particular brand of weak ideological commitment rather than commitments to ideals. These signifiers, for many men on the right, are altogether a clear and apparent performative masculinity that selects for state violence and dominance over women, a stark contrast from how matcha drinking urban men might be called out for performatively reading bell hooks or listening to Faye Webster over corded earphones.

Closing Thoughts

Patel’s newest coin does look like a cheap, edgy bottle opener or belt buckle that one could buy from a mall kiosk. There’s perhaps an apt association for a White House administration covering the Oval Office in gaudy gold and an FBI director who just a few weeks ago told his deceased "brother" Charlie Kirk "We have the watch, and I'll see you in Valhalla." Individually, each of these actions is exceptionally corny or cringe, but as a whole they indicate the importance of performing tough guy aesthetics for the Trump White House and its base alike.

This has gone unsaid here so far, but there is also a specter of whiteness that is pervasive both through Patel's challenge coin and the aesthetic miasma from which it plucks its design elements. I don't think this is solely on the shoulders of Kash Patel, an Indian-American man, but even the Senate Committee on the Judiciary has highlighted his praise for white extremists and the NAACP condemned his Senate confirmation. Patel is not alone among far-right Indian-American demagogues, who have proven their kinship with radical and mainstream white supremacy time and time again. Both Savera and Political Research Associates (who often write together) have documented and explained these dynamics. There is a lot of power in performing this dudecore masculinity, and that power overlaps significantly with white supremacist sensibilities, however intentional or tacit this support might be.

The security state under Trump is roiling with a truly pathetic ultramasculine performativity. The visual identity of this subculture is something I’ve been documenting for over a decade in my own writing. Therefore, while it’s nothing new, it’s worth commenting on how this form of performative male is at once in line with dominant conservative views on gender roles and also deeply connected with state power – neither of which is true of the performative male identity that I led this essay discussing.

Many thanks to Robin for thoughtful edits on an earlier draft. All mistakes, however, are my own.